Gujarat vs West Bengal Navratri: How two states celebrate the same Festival completely in different manner

On the same October evening, a family in Ahmedabad prepares for nine nights of Garba dancing, while a family in Kolkata plans their pandal-hopping route. Both are celebrating Navratri, both are honoring the divine feminine – yet their festivals will look completely different.

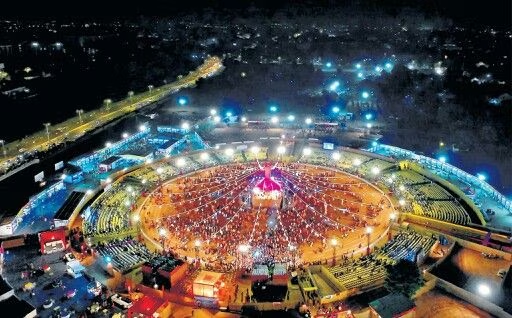

Gujarat’s Navratri is all about dancing your devotion (Garba) – grounds filled with colorful circles, everyone moving to the beats. But if we head to Bengal during the same time, and you’ll find something totally different: massive artistic installations, elaborate feasts, and celebrations that feel more like cultural festival. Both are celebrating the same nine-night festival honoring the divine feminine.

Yet if you dropped someone from Gujarat into a Kolkata Durga Puja celebration or vice-versa, they might wonder if they’re even at the same festival. The beauty lies in how differently we can honor the same spiritual energy – through dance and discipline in Gujarat while through art and abundance in Bengal.

Gujarat's Navratri - Dance as Devotion

Walk into any Gujarati neighborhood during Navratri, and you’ll witness something magical. Empty plots and community halls transform overnight into vibrant Garba grounds, decorated with colorful lights and rangoli patterns. Garba originated in Gujarat as a devotional dance during Navratri. People placed a clay pot with a lamp (symbolizing the womb and divine energy) at the centre and danced in a circle around it, singing in praise of the Mother Goddess. The round movement reflects the Hindu idea of life’s cycle – birth, life, death, rebirth with the Goddess as the constant centre. Over time, it became a joyful cultural tradition spread far beyond Gujarat.

Months before the festival, neighborhood committees form organically. Uncle Ramesh becomes the music coordinator, Meera aunty handles decorations, and the local youth take charge of crowd management. Everyone contributes – whether it’s time, money, or simply showing up every night. This isn’t a spectator sport; participation is the point.

What’s fascinating is the discipline woven into this celebration. Most Garba dancers observe fasts during the day, eating only one meal after evening aarti. They’ll dance for hours, sometimes until 1 AM yet return the next evening with the same energy.

—> stay healthy Navratri food energy <— (link for post)

Bengal's Navratri - Where Creativity Becomes Prayer

Meanwhile, in Bengal’s narrow lanes, Durga Puja unfolds as a completely different kind of devotion. Here, the goddess doesn’t live in a simple clay pot but in elaborate temporary structures called pandals that can rival art galleries in their creativity and craftsmanship.

Kumartuli clay artists begin sculpting Durga idols weeks in advance, their skilled hands shaping clay into divine forms that seem to breathe with life. Theme committees debate concepts that will make their pandal stand out- some recreate famous monuments, others tackle social issues, and a few transport visitors to mythological realms.

The goddess isn’t just worshipped; she’s celebrated through every art form Bengal treasures. Durga Puja started as a worship of Goddess Durga’s victory over Mahishasur, symbolising the triumph of good over evil. Its roots are in eastern India. Records show royal and landlord families performing it during Sharad Navratri- an unusual time for Durga worship, hence called Akal-Bodhan (untimely awakening of the Goddess). Over time, it shifted from private family rituals to public community celebrations (Baroari or Sarbojanin Puja) during the 18th–19th centuries, blending devotion, art, theatre and social gathering. Today it is both a religious festival and a cultural highlight not just in Bengal but much of India too.

Both traditions have evolved without losing their essence. Gujarat’s Garba now includes international participants and fusion music, while Bengal’s pandals incorporate contemporary themes and modern technology. Yet the spiritual core – that sense of coming together to honor something greater than ourselves – remains beautifully intact.

This is what makes Indian festivals so remarkable. The same devotional energy can express itself as rhythmic dance in one state and artistic magnificence in another, proving that there are infinite ways to touch the divine.

How History Shaped Two Different Navratris?

The Ancient Roots That Grew Different Branches

Navratri’s story in India goes back over a thousand years, but here’s what’s fascinating – the same ancient texts that describe goddess worship ended up creating completely different celebration styles in Gujarat and Bengal. It’s like watching the same seed grow into two entirely different trees.

In Gujarat, Navratri traditions trace back to the Chalukya and Solanki periods when communities would gather for group prayers during harvest time. The circular dance wasn’t invented for entertainment – it was a practical way for large communities to pray together, with everyone equally distant from the central flame or deity. The word “Garba” itself comes from “garbha” meaning womb, representing the feminine creative force. Historical texts from the 12th century describe how Gujarati communities would place a clay pot with a lamp inside (symbolizing life in the womb) at the center of their worship circles.

Bengal’s Durga Puja took a completely different historical path. While goddess worship existed here for centuries, the modern Durga Puja format actually began in the 1600s when wealthy Bengali families started hosting elaborate household celebrations. The British colonial period inadvertently shaped today’s community pujas– when the East India Company’s policies disrupted traditional family structures, neighborhoods began organizing collective celebrations instead.

The Geography Factor That Changed Everything

Gujarat’s landscape – with its open spaces and trading community culture – naturally supported large group activities. The state’s history as a major trade hub meant communities were already used to organizing collective events for business and social purposes. When Navratri came along, applying that same organizational skill to religious celebration was natural.

Bengal’s monsoons shaped everything differently. Elaborate pandals weren’t just art – they were practical waterproof shelters for unpredictable weather, then evolved into artistic showcases. The competitive spirit reflects Bengal’s deep cultural tradition of celebrating intellectual and creative achievement.

The Festival Mechanics: How Each Celebration Actually Works

Navratri in Gujarat operates like a well-oiled community machine. Every Garba ground has its informal hierarchy – not based on wealth or status, but on commitment and skill. The “Garba organizers” emerge naturally from people who’ve been consistent participants for years. They handle everything from sound systems to crowd flow, creating events that can accommodate thousands while maintaining order. The dance itself has sophisticated mechanics that aren’t obvious to outsiders. Garba circles move clockwise, starting with movements anyone can follow and building to intricate patterns that require skill and practice.

Modern Gujarati Navratri has embraced technology and globalization while keeping its community focus. Professional event management companies now handle logistics for major Garba ground. International Garba events from New Jersey to Singapore follow the same basic structure as village celebrations in rural Gujarat.

—> (Navratri celebration abroad link) <—

Durga Puja operates more like a cultural production company. Each community puja has specialized committees – theme planning, idol making, cultural programming, food coordination, and crowd management. The timeline stretches across months, with peak intensity in the weeks before the festival.

The pandal construction process is fascinating engineering. These temporary structures often cost lakhs of rupees and require permits, architectural planning, and skilled labor. Many incorporate complex lighting, sound systems, and climate control. Some pandals are so elaborate they attract visitors from other states, turning religious celebration into cultural tourism.

Amba and Durga: Different Facets of the Same Power

When Gujaratis chant “Amba Mata ki Jai” and Bengalis cry “Joy Ma Durga,” they’re invoking the same cosmic energy through different cultural lenses. Understanding these variations isn’t about comparison – it’s about appreciating how the infinite divine feminine manifests uniquely across regions.

Amba: The Nurturing Mother Energy

In Gujarat’s Navratri tradition, Amba represents the maternal aspect of the goddess – the protective, nurturing force that guides her devotees like children. The very act of Garba dancing around the central pot symbolizes children circling their mother, seeking her blessings and protection. Ambe mata’s worship emphasizes discipline and devotion through joyful surrender. The fasting during the day followed by energetic dancing at night mirrors a child’s relationship with a loving but firm mother – accepting restrictions because they come from a place of care. The circular formations represent the cycle of life that the divine mother oversees, from birth to death to rebirth.

Durga: The Warrior Goddess of Justice

Bengal’s Durga embodies the fierce warrior aspect of divine femininity – the protector who destroys evil to restore cosmic balance. The elaborate pandals and artistic installations reflect this powerful energy, creating spaces worthy of a goddess who commands both reverence and awe. Durga mata’s ten arms, each holding different weapons, represent her complete power over all aspects of existence.

The four-day celebration pattern follows the narrative of Durga mata’s arrival, her battle with evil forces, her victory, and her return to her divine abode. Each day carries specific spiritual significance.

What’s beautiful is how both forms address the same human spiritual needs through different approaches. Ambe maa’s maternal energy provides comfort, guidance, and community connection. Durga mata’s warrior aspect offers strength, justice, and protection from negative forces. Both teaches us to surrender to maternal divine will while actively participating in their spiritual growth. The regional differences reflect deeper cultural values too.

Gujarat’s emphasis on community discipline and joyful participation mirrors its trading heritage where collective success depended on everyone contributing equally. Bengal’s focus on artistic expression and intellectual discourse reflects its rich literary and cultural renaissance traditions.

Whether you’re seeking the nurturing embrace of Amba Mata or the empowering strength of Durga Maa, both paths lead to the same destination, a deeper connection with the goddess and an energy that creates, sustains, and transforms our lives.

JF’s Concluding Ode

From Garba to grand pandals we roam,

Each state makes the goddess feel home.

One dances with grace, one builds sacred space,

Both honor Her power; Her love we embrace,

We can conclude that Gujarat’s rhythmic Garba and Bengal’s artistic Durga Puja prove that devotion has no single form. Whether through disciplined dance or elaborate pandals, both states honor the same divine feminine energy while preserving their unique cultural identities. These beautiful differences remind us that India’s festival traditions don’t divide us – they showcase the infinite ways communities can celebrate, connect, and find the sacred in joyful celebration.